The Connecticut River spans 410 miles across four states

The river is home to millions of fish and other species.

Use the map to learn more about the barriers these fish face and how they move around them.

Mary Steube

About the facility

There is a fish ladder on the property next to the dam on Lower Mill Pond. The fish ladder was built in 1998 through a cooperative effort between the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) and the Old Lyme Land Trust. The fish and eel ladder operation is monitored by the CT DEEP, which issues weekly fish count reports during the fish run season. The fish ladder has a viewing window where it’s possible to see the fish go up the ladder. There is a fish counter on the ladder to keep track of the number of fish using it.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

How are they moving?

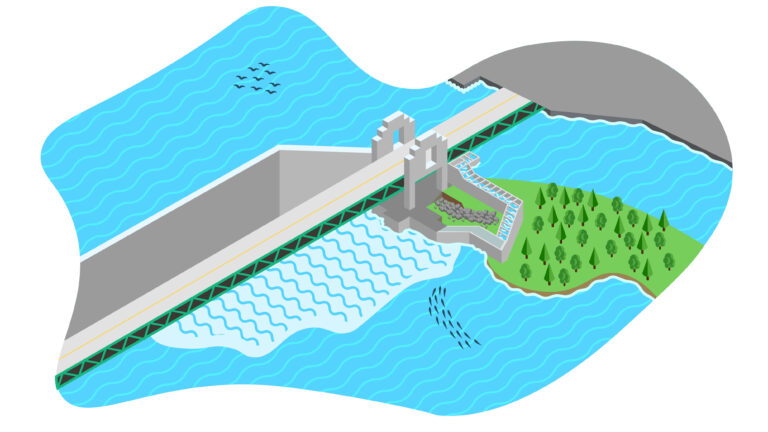

At the Mary Steube facility, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. At this site there is also an eel ladder. The eel wrap around the pegs as they move upward. Unlike the fish ladder, the eel ladder does not span the height of the dam. The eel drop into a bucket after traversing the ladder and are deposited in the pond by DEP staff. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The Mary Steube fish ladder does not have specific viewing hours. When in operation, the public can view fish using the ladder by visiting the Griswold Preserve. There is no cost of admission. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Mary Steube

30 Boston Post Road

Old Lyme, CT 06371

Rogers Lake

About the facility

The construction of the Rogers Lake fish passage facility in 2014 enabled the return of migratory fish to Rogers Lake in Old Lyme for the first time in several hundreds of years. The new ladder at Rogers Lake was part of a larger project to restore the concrete dam at the lake and was a partnership between the town, Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) and the Connecticut River Conservancy. The addition of the ladder created passage up the Mill River and opened up spawning habitat.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

How are they moving?

At the Rogers Lake facility, fish move upstream by using the 20-foot fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The fish ladder at Rogers Lake does not have specific viewing hours. When in operation, the public can view fish using the ladder by visiting Rogers Lake. There is no cost of admission. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Rogers Lake Dam

Old Lyme, CT 06371

Moulson Pond

About the facility

The Moulson Pond Fishway on the Eightmile River has successfully provided passage for migrating fish and eels around the old mill dam for many years. Since 1998, when the fishway was installed, thousands of fish have been observed passing around the dam to swim upstream to their ancestral spawning grounds. Since 2015, a newly installed camera has been able to give Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP) an accurate count of the fish that traveled this way. The fish ladder operation is monitored by the CT DEEP, which issues weekly fish count reports during the fish run season.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

How are they moving?

At the Moulson Pond facility, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The Moulson Pond ladder does not have specific viewing hours. When in operation, the public can view fish using the ladder by visiting the fishway. There is no cost of admission. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Moulson Pond

26-2 Mt Archer Rd

Lyme, CT 06371

Leesville Dam

About the facility

The Leesville Dam was built on the Salmon River in 1900. It 450 feet wide and 25 ft tall. In 1981 some of the first salmon returns were observed at the Leesville Dam. The fish ladder operation is monitored by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP), which issues weekly fish count reports during the fish run season.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

How are they moving?

At the Leesville Dam, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the stepped pools from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The Leesville Dam fish ladder does not have specific viewing hours. When in operation, the public can view fish using the ladder by visiting the dam. There is no cost of admission. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Leesville Dam

Moodus, CT 06469

StanChem Dam

About the facility

The StanChem fish ladder was built in 2013 to allow fish to swim upstream around the dam that was built in 1900. The passageway opened the upper 15 miles of the Mattabesset River to native migratory fish populations. The fishway, built in partnership with property owner Stanchem Corp and several nature advocacy non-profits, is on Stanchem property in the East Berlin section of Berlin. The fish ladder operation is monitored by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP), which issues weekly fish count reports during the fish run season.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the StanChem Dam, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The StanChem Dam fish ladder is not open to the public. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

StanChem Dam

401 Berlin St

Berlin, CT 06023

Rainbow Dam

About the facility

Dams along the Farmington River have been using the rivers power to generate electricity since the early 1800s. The current fish ladder at the Rainbow Dam, which consists of a series of 59 interconnected pools, was constructed in 1976 to make it possible for anadromous fish to return upriver to spawn. A new fish passageway for Rainbow is currently in the design stage.

In 2023, CT DEEP did not operate the Rainbow Fish Ladder due its documented poor performance and the lack of suitable downstream fish passage protection measures at the Stanley Works owned dam/project. Fish passage at this project has been the responsibility of the CTDEEP, due to FERC legal rulings and timing of that facilities construction.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the Rainbow Dam, fish move upstream using several methods. Many pass upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. At this site there is also an eel ladder. The eel wrap around the pegs as they move upward. Unlike the fish ladder, the eel ladder does not span the height of the dam. The eel drop into a bucket after traversing the ladder and are deposited above the dam by fishway staff. To move downstream, fish at this site either go over the dam spillway or through a bypass around the dam.

Where and when can I see them?

The fish ladder at Rainbow Dam is open to the public during the migration season on open house days. The outdoor portion of the ladder is open year-round, but the indoor viewing station is only open during open houses. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Rainbow Dam

Windsor, CT 06095

West Springfield Dam

About the facility

Prior to the construction of the fishway in 1951, the West Springfield dam (formerly known as DSI dam) was the first barrier on the Westfield River that migratory fish would face and couldn’t pass. The fishway was built as a result of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) relicensing process and first opened in 1996. In 2001, an eelway was constructed at the fishway, allowing the American eel to migrate upstream of the dam as well. Passage of fish at the West Springfield Dam opened approximately 20 additional miles of habitat in the mainstem Westfield and much more in the tributaries. The MA Division of Fisheries and Wildlife is responsible for monitoring the fishway.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the West Springfield Dam, fish move upstream using several methods. Many pass upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. At this site there is also an eel ladder. The eel wrap around the pegs as they move upward. Unlike the fish ladder, the eel ladder does not span the height of the dam. The eel drop into a bucket after traversing the ladder and are deposited above the dam by fishway staff. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

The fish ladder at the West Springfield Dam (formerly known as DSI dam) is not open to the public during the migration season apart from a once-a-year open house. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Westfield River Reservoir

Agawam, MA 01030

Holyoke Dam

About the facility

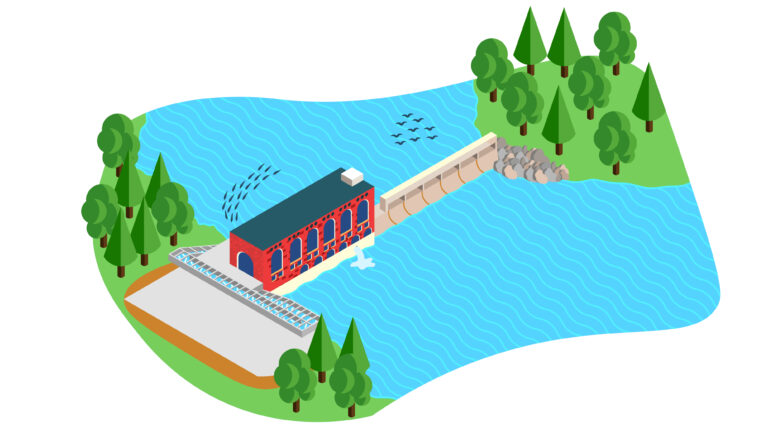

The Holyoke Dam is a granite dam that spans the Connecticut River between Holyoke and South Hadley and diverts water from the river into the Holyoke Canal System and Holyoke Gas & Electric’s (HG&E) Hadley Falls Facility. The dam that you see today was constructed between 1895 and 1900. The Hadley Falls Facility is located on the Holyoke side of the Holyoke Dam and contains two hydroelectric generating wheels with a total installed capacity of approximately 33 megawatts. Hadley Falls also houses a fish lift to help fish traveling upstream pass over the dam, and is open to the public for Fishway viewing and tours during the public viewing season.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the Holyoke Dam, fish move upstream primarily using a fish elevator. With this elevator, fish swim into a collection area at the base of the dam. When enough fish enter the collection area, they are moved into a hopper that carries them toa flume that empties above the dam. At the Holyoke Dam, two elevators lift 500 fish at a time up the 52 foot dam. At this site there is also an eel ladder. The eel wrap around the pegs as they move upward. Unlike the fish ladder, the eel ladder does not span the height of the dam. The eel drop into a bucket after traversing the ladder and are deposited above the dam by fishway staff. To move downstream, fish at this site either go over the dam spillway or through a bypass around the dam.

Where and when can I see them?

The Robert Barret Fishway at the Holyoke Dam is open to the public during the migration season, but visitors must reach out via their online form to request a tour. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Robert Barrett Fishway

1-3 County Bridge

Holyoke, MA 01040

Tel: (413) 536-9460

Email the Fishway

Easthampton Dam

About the facility

Built in 2014, the fish ladder in Easthampton has performed well in attracting migratory species that had been absent from the Manhan River after dams reduced their ranges. The fish ladder operation is monitored by US Fish and Wildlife, which issues weekly fish count reports during the fish run season.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the Easthampton Dam, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. To move downstream, fish at this site go over the dam spillway.

Where and when can I see them?

Public access to the fish ladder remains limited on a drop-in basis, though according to the city, the facility is readily accessible upon request. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Easthampton Dam

39 Northampton St

Easthampton, MA 01027

Turners Falls Dam

About the facility

The Turners Falls ladders help migrating fish get past the Turners Falls dam. These stair-like ladders consist of a series of rising pools, each pool approximately one foot higher than the last. Completed in 1980, the Turners Falls ladders are a series of three ladders located along a 2.5-mile stretch of the river. The Turners Falls ladders are located at the Cabot Hydroelectric Station, the spillway (dam) and the gatehouse.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

How are they moving?

Fish enter the fishladder at Cabot station, or continue upstream to a second ladder at the dam. If they enter here, they travel upslope using a series of stepped pools to reach the power canal, where they can continue swimming upstream. To move downstream, fish move over the spillway when there is water or out through the power canal.

Where and when can I see them?

The Turners Falls Fishway lets visitors see what fish look like underwater as they swim upstream. The fish ladder is open for public viewing during the height of spawning season from mid-May to mid-June. Admission is free.

(behind the Montague Town Hall)

1 Avenue A

Turners Falls, MA 01376

Vernon Dam

About the facility

The Vernon Dam was built in 1909, and its primary use is to generate hydropower by harnessing the power of the river. The fish ladder at the Vernon Dam became operational in 1981 and provided upstream access for migratory fish. The dam is owned and operated by Great River Hydro. The fish ladder at Vernon Dam is to the left of the powerhouse.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the Vernon Dam, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the ladder from the base of the barrier to the waters behind. At this site there is also an eel ladder. The eel wrap around the pegs as they move upward. Unlike the fish ladder, the eel ladder does not span the height of the dam. The eel drop into a bucket after traversing the ladder and are deposited above the dam by fishway staff. To move downstream, fish at this site either go over the dam spillway or through a bypass pipe around the dam.

When and where can I see them?

The outside viewing platform at the Vernon Dam fish ladder is open to the public during migratory fish season. There is no indoor viewing open to the public. Local organizations and companies sometimes run tours at the fishway. The fish ladder is located at the following address:

Vernon Dam

110 Governor Hunt Rd

Vernon, VT 05354

Bellows Falls Dam

About the facility

In the 1920s, the present concrete dam and hydroelectric powerhouse were constructed in Bellows Falls, VT. The fish ladder was completed in 1982 in an effort to reintroduce migratory fish species to the reaches of the upper Connecticut River and its tributaries. The dam is owned and operated by Great River Hydro. Just above the powerhouse is a visitor’s center with information about fish migration and local history.

Who passes through this dam?

When do fish migrate?

Upstream

Downstream

How are they moving?

At the Bellows Falls Dam, fish move upstream by using the fish ladder. With stepped pools of flowing water, fish can hop up the stepped pools from the base of the barrier to the waters behind.

To move downstream, fish at this site either go over the dam spillway or through a bypass around the dam.

Where and when can I see them?

The fishway at the Bellows Falls Dam is open to the public during migratory fish season. Bellows Falls Dam has a visitors center with information about fish migration and a viewing window and platform. To contact via phone, call the direct line to the center during the open season on open days from 10:00AM – 4:00PM at 802-460-4664.

17 Bridge St

Bellows Falls, VT 05101

The Connecticut River

New England’s longest river runs from the Canadian border through New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts and Connecticut and then all the way down to the Long Island Sound.

The watershed encompasses 11,260 square miles, with 148 tributaries, including 38 major rivers and numerous lakes and ponds. Its waters, woods, and wetlands provide nationally recognized fish and wildlife habitat.

In 1997 the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge was established to conserve, protect and enhance the abundance and diversity of native plant, fish and wildlife species and the ecosystems on which they depend throughout the 7.2 million acre Connecticut River watershed. The refuge was designed to include the entire Connecticut River watershed because legislators realized that, in order to protect migratory fish and other aquatic species, there was a need to protect the whole river system and its watershed. The health of any aquatic ecosystem is linked to the health of the whole watershed upstream.

Other dams

There are over 1000 dams in the Connecticut River Watershed. The dams listed above are the dams along the Connecticut River, or along its tributaries that count fish passage. Other dams on the Connecticut River include the Enfield Dam (breached), the Wilder dam, the Ryegate dam, the McIndoe Station dam, the Comeford Station Dam, the Moore Reservoir dam, the Gilman Project dam, the Groveton Dam (breached), the Lower Canaan Dam, the Murphy dam, the 1st CT Lake dam, 2nd CT Lake dam and the Moose Falls dam. There are hundreds of dams not listed above that exist on tributaries of the Connecticut River.

A healthy river won’t happen overnight

After decades of neglect, the native populations of migratory fish are making a comeback in the Connecticut River watershed. Progress, however, takes time. Efforts that began in the 1960s-80s have greatly influenced the health and return of these native species. Efforts today work to ensure that populations continue to increase into the future.

Habitat degradation:

what’s gone wrong?

Decades of dam building, pollution and overfishing led to the decimation of native migratory fish populations in the Connecticut River. The loss of primary habitat, whether it became unreachable, or simply unsuitable, has continued to suppress the recovery of these populations. Restoring habitat and removing dams is a step towards ecological abundance.

Habitat restoration:

what we’re doing today

Effective habitat restoration can take many forms. When possible, removal of dams and culverts opens rivers and streams for fish, while fish passage structures allow movement when removal is not viable. Planting trees along rivers shade water for fish and provide important inputs into the aquatic food chain.

Regional efforts:

how you can help

Work throughout the watershed is completed by many state, federal, tribal, nonprofit, and community partners working together to protect and promote fish populations. Community involvement in the form of tree planting, fish counting and public outreach is necessary for river restoration.